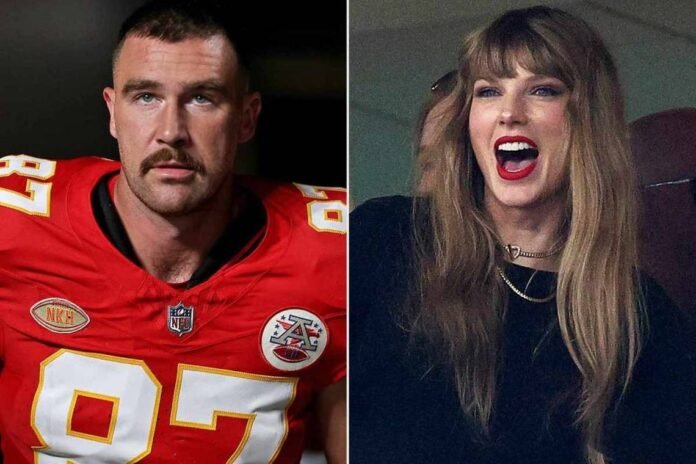

In July of last year, an estimated 50,000 fans flooded Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City to see Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour concert. Among those in the crowd was football tight end Travis Kelce, eager to woo Swift.

Arrowhead has been central to Swift and Kelce’s romance ever since: After making their romance official last September, Swift has routinely joined the 76,000 Chiefs fans to cheer for Kelce and his teammates. From concertgoers to sports spectators, the thought of that many people in the same space is difficult to imagine. Equally hard to imagine, and significantly more heartbreaking, Israel Defense Forces have killed 25,000 Palestinians since Oct. 7, 2023; that number of people would fill about a third of Arrowhead Stadium.

This is a jarring image, but such is the reality of our present moment: While the state of Israel carries out a genocide against Palestinians, we are easily distracted by our adoration for Swift and Kelce, along with spectator sports. That we are this preoccupied with celebrity romance is no coincidence but, in fact, a main feature of our neoliberal society. Instead of imagining love as a concrete, revolutionary political practice, we are enamored by its simulacrum.

It’s not a surprise that one of the biggest sensations of our current popular culture involves Swift and her romantic endeavors. Love songs have been good for Swift’s bottom line — and her own love life is no exception.

Having dominated the music industry for almost two decades and amassing over $1 billion in net worth, Swift’s songwriting has continuously invited the public into her most intimate relationships over the years. Whether “love’s a game” (“Blank Space”) that she beckons others to play with her, or love is the thing she’s “spent [her] whole life trying to put it into words” (“You Are In Love”), romantic love has been part and parcel to Swift’s identity as a musician.

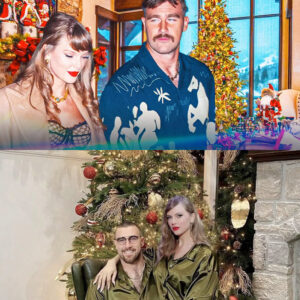

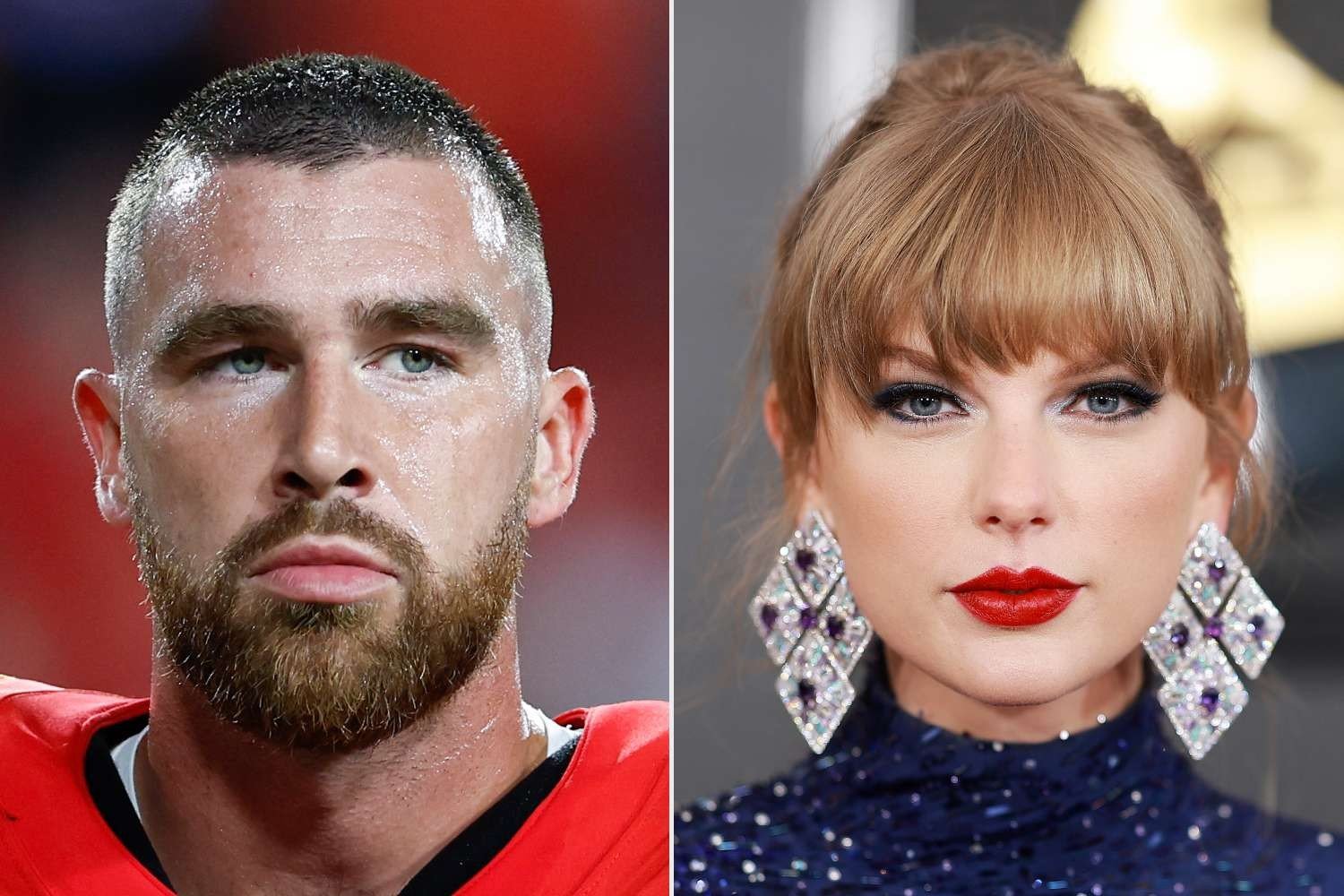

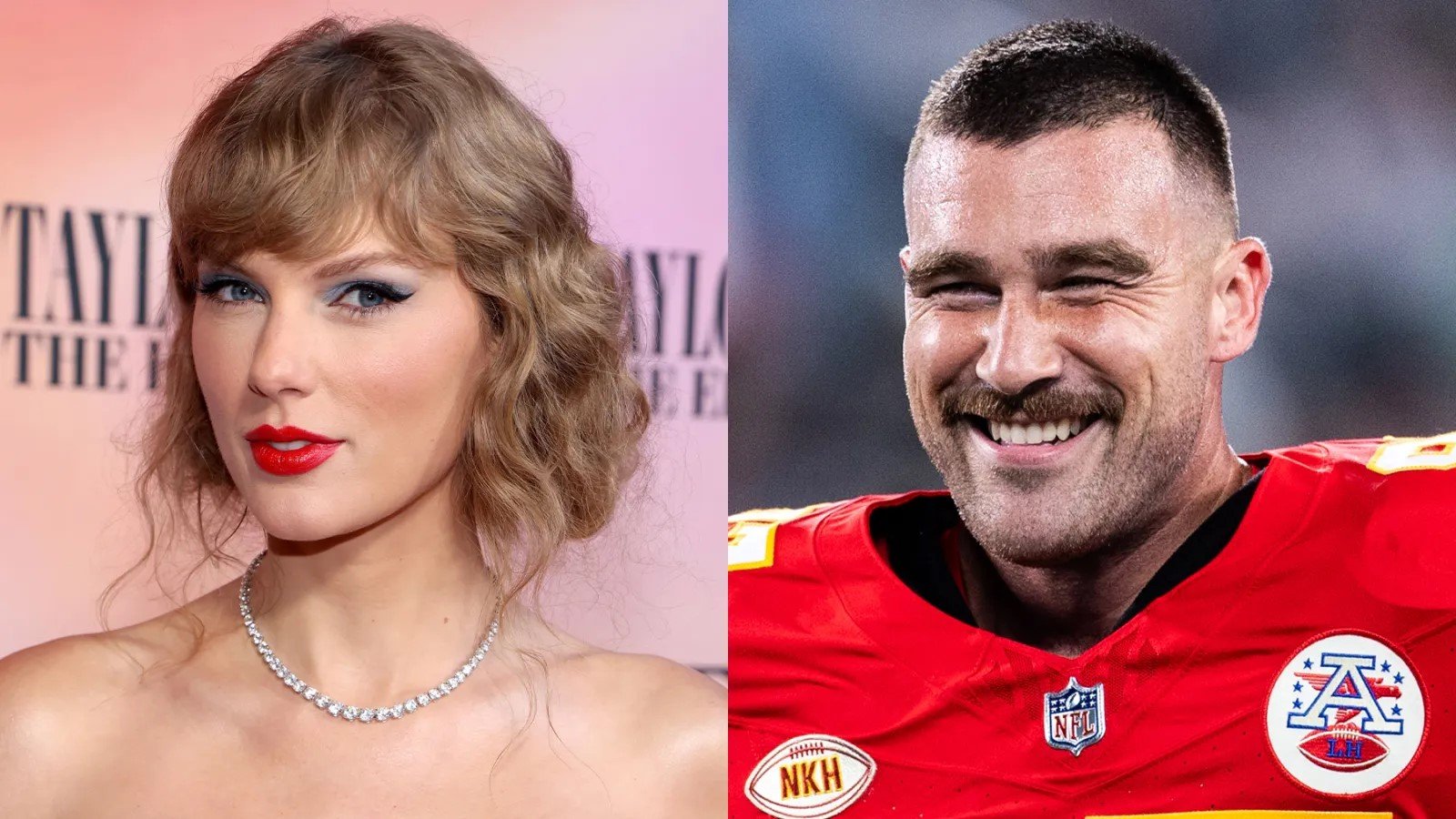

Her most recent — and arguably most public — romantic relationship proves no different. Since Swift and Kelce made their romance public last September, they have been gifted the celebrity portmanteau, ‘Swelce,’ and have also been given a premium opportunity to capitalize on their popularity both as individuals and as a couple.

Inspiring everything from memes to the colors of the Empire State Building, the material evidence of our obsession with celebrity culture is evident in the spike of Chiefs jersey sales and the projected $5 million Kelce could gain in off-the-field earnings thanks to his involvement with Swift. In her youth, Swift once sang, “In your life, you’ll do things greater than dating the boy on the football team.” And yet, 15 years later, at a live show in Buenos Aires, she changed the lyrics of her song “Karma” to, “Karma is the guy on the Chiefs, coming straight home to me.”

In light of these monetary gains, the couple has been sure to keep up appearances: Swift has diligently attended the Chiefs football games throughout the season — including a frigid playoff game in January that was reported to have garnered the largest streaming audience ever. Looking to expand its audience, the NFL has taken every opportunity to show Swift in attendance. And yet, as we Americans obsess over the flourishing of an “all-American” love story, we’ve neglected to turn equal attention to a modern genocide. Why is it so easy to turn away and how do we resist this temptation?

In her book Religious Resistance to Neoliberalism, Keri L. Day argues that neoliberalism must not only be understood as an economic model but also as a cultural and political one. As a professor of constructive theology at Princeton Theological Seminary, Day understands neoliberalism as a “type of rationality and governmentality” that reshapes individuals into “enterprises.” In other words, within a neoliberal society, individuals can make businesses out of themselves, cashing in their established fame for endless fortune and providing consumers with endless distractions.

Begrudgingly or not, we’re all complicit in upholding celebrity enterprises. Swift and Kelce are masters at turning themselves and their romance into a business, and we are their customers. When thinking about consumerism in a neoliberal society and how obsessed with celebrities’ romantic lives we’ve become, it’s important to recognize what this does to our moral systems and understandings of love. Day writes: “The horror of neoliberal societies is that it defines the good and beautiful in terms of profit rather than in terms of human connection and care.”

Relative Articles

None found